Welcome to new subs + thanks a million for the WebGPU love! This thing has grown a whole lot faster than my inner pessimist could have imagined. So, grazie!

If you enjoy these primers, I’d appreciate it if you favourite this post’s tweet to help spread the good (?) word of Why Now!

As always, I’m at alex@tapestry.vc should you ever wish to chat.

Many smart friends are 50/50 on cybersecurity as a pre-seed/seed investment category. I have always been perplexed by this.

From my vantage-point, security is one of the few categories where actors are just as incentivised to “innovate” on problem vs. solution creation. Thus, upstarts are provided with wedges to take on incumbents.

The second criminally under-discussed topic in the world of technology investing is cybersecurity’s role in the “Why Now” market equation.

Without asymmetric encryption (the “s” in https) the modern internet as we know it wouldn’t have thrived. Talk about a firm grip (..sorry) on innovation! There’s more:

Pioneering remote-first companies (a la GitLab) without VPNs (+ perhaps SSH) would likely have struggled to operate. Would Deel be a company?

The emerging “isolate cloud” (Deno, Grafbase, etc) is partially a second-order outcome of Chrome’s need to sandbox untrusted code.

Microservices wouldn’t have proliferated to the same degree without service meshes a la Envoy. (& more recently, eBPF).

And, as I’ve written [1][2] about previously, broad-scale personalised ML models will not be “a thing” (technical term) without privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs).

Ok, point proven. So what’s next in cybersecurity?

Famous last words, but the “final frontier” has always been to encrypt data across its three states: at-rest, in-transit & in-use.

Why? Because if sensitive data like your FullName is perennially encrypted (e.g., “De2CYsx”) it’s rather difficult for a malicious actor to do anything untowardly.

Conveniently, how we secure data in-use has three “states” also: fully homomorphic encryption (FHE), trusted platform modules (TPM), and secure enclaves.

As you may have ..deciphered.. from the title of this primer, we’ll be delving into secure enclaves — the approach many hardware (Intel/AMD) + software/cloud (AWS/Azure) giants are hanging their hats on.

Within this primer we’ll discuss:

A ~brief history of encryption.

Approaches to data in-use security.

Secure Enclaves. You’d hope!

Thanks to friends Nev, Liam & Liz at Evervault for the inspiration for this post + for reviewing!

Yes, the above caption was my attempt of humour! .. just subscribe?

Secure Enclaves are highly-constrained compute environments that allow for cryptographic verification (attestation) of the code being executed.

As always, let’s cherry-pick the complexity out of this definition & take it step-by-step. First, some history.

Encryption — A Brief History (2023), Alexander Mackenzie

Cryptography is the practice & study of techniques of secure communication in the presence of adversarial behaviour.

Encryption is the process (& in many ways, art) of scrambling data so that only authorised parties can understand the underlying information. So yes, encryption is a subset of cryptography.

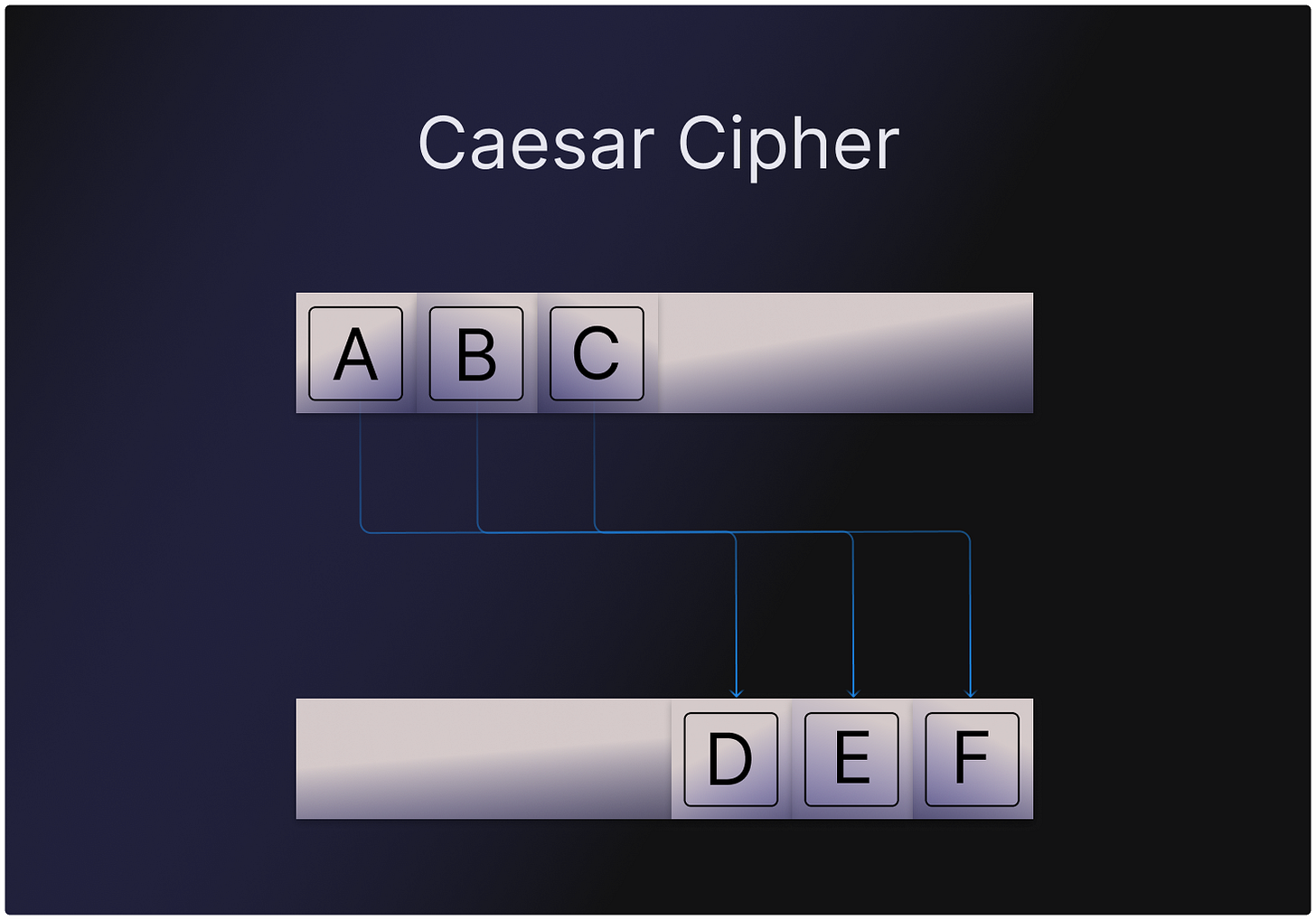

In and around 100BC Julius Caesar was slinging secret messages around Caput Mundi (aka Rome) via a relatively simple substitution “cipher” (ie encrypt/decrypt function) now known as the “Caesar Cipher”.

This was a relatively simple “shift-by-three” cipher. Meaning that the letter “A” would be substituted with the letter “D”, the letter “X” would be substituted with “A”, etc.

What’s pertinent here is that Caesar Cipher is rule-based encryption. Once someone knows the rules of the game they can easily decrypt the “ciphertext” (encrypted text) into “plaintext” (decrypted text).

Astute readers will note that if letters such as “D” or “L” appear frequently in Caesar’s ciphertext, that these letters likely map to plaintext vowels (A and I respectively).

Similarly, readers may look for common bigrams (sequences of letters) in words such as: NG, ST, QU, etc. This strategy is known as “frequency analysis”. Not exactly an unbreakable code.

** Modern encryption wasn’t built in a day either! … **

Modern encryption tends to rely on what’s known as an “encryption key” (or key*s*) which stems from the work of ~Blaise de Vigenère in the 16th century.

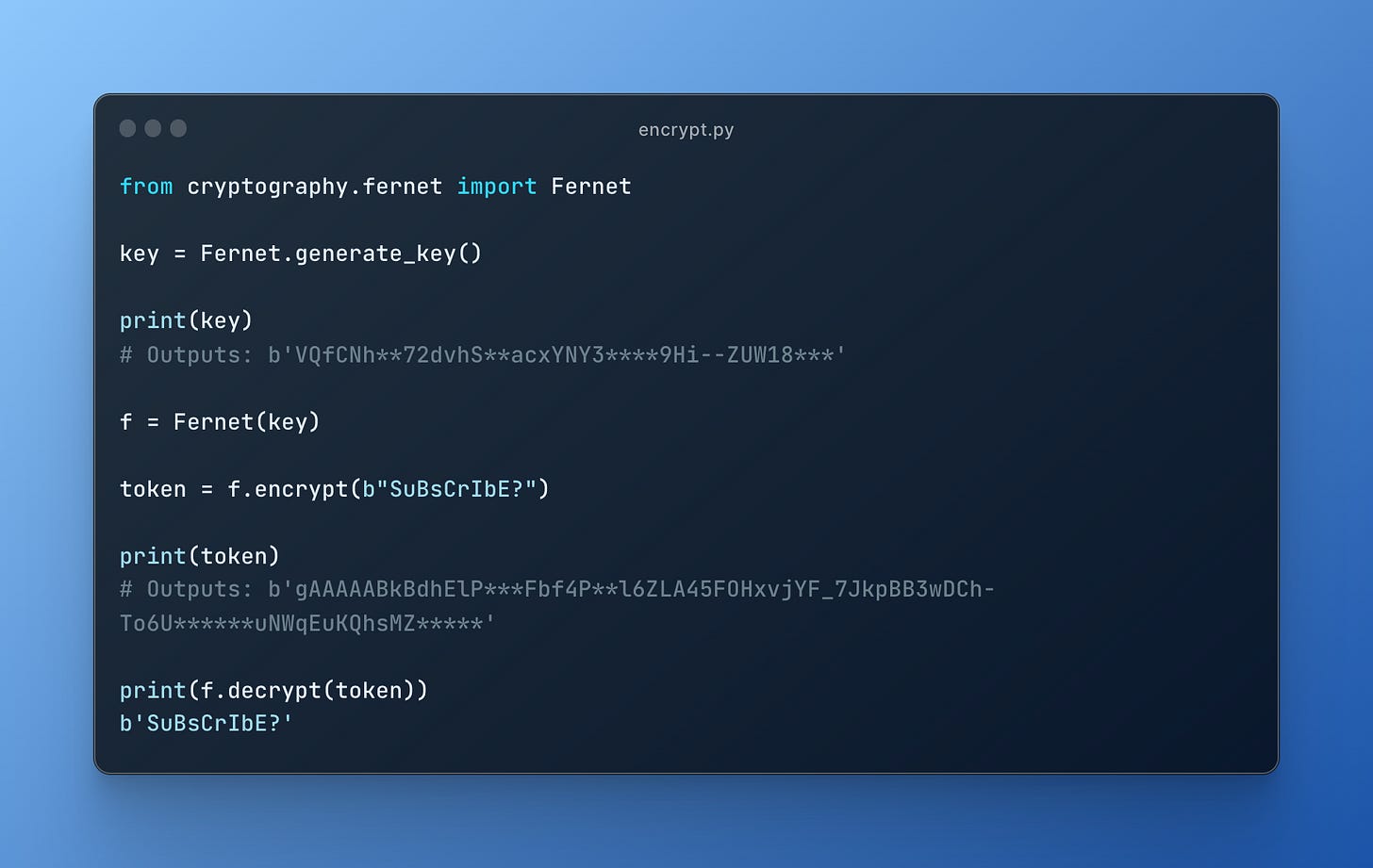

Encryption keys are a hard-to-guess string of letters, numbers and symbols such as: b'VQfCNh**72dvh that, when combined with a secret message, produce a unique output.

Below I used the python cryptography library to:

Generate an encryption key

Encrypt a message (“SuBsCrIbE”.. subtle) with this key

Print the ciphertext

Decrypt the ciphertext with the key & print the resulting plaintext

Technical Detail: When a single encryption key is used to both encrypt & decrypt data this is known as “symmetric encryption”.

When alternate keys are used to encrypt (public key) and decrypt (private key) data this is known as “asymmetric encryption”.

Vigenère used symmetric encryption to make his cipher “polyalphabetic” — whereby each plaintext character (e.g., “C”) was combined with an encryption key character (e.g., “H”) in order to “generate” a character (“J”) from a specific alphabet.

Example below:

However, this method and its 19th/20th century successors (including the German Enigma rotor machine!) once again eventually fell short when frequency analysis was used.

** I’m oversimplifying what it took to crack Enigma to the nth degree here! **

Fast-forward to the 1970s and IBM designed a cipher (remember, an encrypt/decrypt function) named Lucifer. A bit.. disconcerting?

Yet, despite this, the cipher was later adopted by NIST (National Institute of Standards & Technology) as a US national standard and (thankfully) renamed to the Data Encryption Standard, or “DES”.

Elsewhere in the 1970s (1976) our friend asymmetric encryption (remember, public and private keys) began to bloom thanks to Whitfield Diffie & Martin Hellman. The advent of asymmetric encryption marked the dawn of “modern” cryptography.

Key Point: Thanks to asymmetric encryption, parties no longer need a shared secret (encryption key) to securely communicate.

Alice can share her public key with Bob in order to encrypt a “secret message” from Bob, but she never has to share her private (decryption) key with him.

Take a second to internalise this as it’s important!

Shortly after (1977), fuelled by Manischewitz (worth looking into), Rivest, Shamir and Adleman released the RSA asymmetric cipher. Yes… like the conference. RSA is the most popular / widely understood asymmetric encryption system to date.

However, as I alluded to in this primer’s opening paragraph: the incentive to create new problems in cybersecurity is high. Come 1997, DES was cracked. Symmetric encryption needed a new saviour.

How was it cracked? Well, thanks to Ye Olde “Moore’s Law” clock speeds (see WebGPU primer) improved.

This meant that via sheer brute-force computation (ie trying every possible solution), malicious actors could correctly guess a 56-bit DES encryption key, and hence, access an underlying message.

Thus, in 1997, another RFP was published by NIST for a new national standard. By the second millennium (yes, 2000), a new cipher was adopted known as Rijndael (pronounced rain-dahl) or the Advanced Encryption Standard.

Without getting into the mathematical weeds, one of AES’ main advantages is that it offers 128-bit, 192-bit or 256-bit encryption keys.

For context, even with a supercomputer, it would take 1 billion billion years to crack a 128-bit AES key using brute force attack.

** Cue the “but what about post-quantum cryptography!” outcry **

A fair Q — quantum is/was a very real threat.

In 2016, NIST… you guessed it, put out another RFP for cryptographers to devise and then vet encryption methods that could resist an attack from future quantum computers.

In July ‘22 the first four quantum-resistant algorithms (thank you lattices) were announced (!) which I’m, naturally, paying quite a bit of attention to, but are well-beyond the scope of this primer.

** Encryption - fin **

Secure Enclaves are highly-constrained compute environments that allow for cryptographic verification (attestation) of the code being executed.

Ok — so what does “data in-use” mean. Why is it a particularly difficult problem to solve?

As mentioned, data has three states:

It’s “at-rest” (😢) when it’s idle (e.g., stored in a database).

It’s “in-transit” when sent across a network (e.g., from your phone to the cloud).

It’s “in-use” when it’s being used/processed in some way (e.g., rendering a UI).

The challenge is, when we want to use data we ~can’t keep it encrypted. Why? well, it’s tricky to do some math on a value such as: “De2CYsx”. So, at some point we need to decrypt data if we want to process it.

However, it’s when we end up decrypting ciphertext into plaintext that things get.. precarious. Hence, data in-use security = holy grail (sorry TLS).

Ok, so what have we done about this problem-space to date?

An alternative to secure enclaves is homomorphic encryption (HE). An encryption “scheme” (ie approach) proposed as early as 1978, what a time to be A[iV3 for cryptographers!

HE enables someone to process data (derive a value from it) without ever having to decrypt the data. Think about what this means for a second:

With HE, we can pass some ciphertext (yes, De2CYsx) as an argument of a function that calculates the sum of 2 + De2CYsx and returns the same answer that it would if De2CYsx was decrypted (perhaps a number like 3?). See below:

Pretty cool, huh? However, as perhaps expected in the field of cryptography, nothing is quite as it seems.

Firstly, homomorphic encryption schemes can be partial or “somewhat” vs. full.

Partial (PHE) or Somewhat (SHE) means that only certain mathematical operations (multiplication and/or addition) can be conducted on the ciphertext.

This is fine, but we’re not quite at the promised land here. Computers tend to do a little more than multiplication/addition.

However, come 30 years later and we kinda are. Craig Gentry (& co) came along in 2009 with a fully homomorphic encryption (you guessed it, FHE) scheme. FHE, in theory at least, enables anyone to perform any operation on ciphertext.

Note: Within these primers I typically try to leave no stone unturned when explaining how something works.

For homomorphic encryption I think this would be a mistake. Each homomorphic encryption scheme is nuanced & requires some pretty hardcore math.

If you’re really into your prime numbers (…), check out the Paillier cryptosystem which is an approach I quite enjoyed digging into.

At this point you’re likely thinking — “why isn’t this primer about FHE then?”. Fair.

Well, the issue with FHE is that it requires a meaningful amount of compute and/or time to calculate a new value from ciphertext inputs.

To put this into context, IBM released its improved (!) HElib C++ library for FHE in 2018. A calculation that would take a second to perform using plaintext would take an average of 11.5 days (!) to perform using the 2018 version of HElib.

As a wise individual once loosely said — no person has any time time for that.

Time for this primer’s raison d'être — secure enclaves.

Ok, so an alternative to processing ciphertext is… to process plaintext. Shocker.

However, we know that exposing plaintext is the root of all data security problems. So, what can we do?

Well, we need to first work backwards to understand how this plaintext data may be accessed and by whom. Once we know the threat, we can form a response.

Let’s use AWS EC2 as an example. In its least-flattering light, EC2 is rented “compute” (ie CPU processing).

A given AWS EC2 “instance” is broadly composed of the following components: users (employees/contractors), 3rd party libraries, applications and an operating system. These components are the whom and should not be trusted.

Moving swiftly onto the how. In computing, when we want to process some data or code, our operating system loads this data from “storage” (e.g., a hard drive) to “memory” (ie RAM). The same is hence true for EC2.

In storage our data is “at-rest”, and hence, encrypted. However, when loaded into RAM it’s decrypted so that it can be used. Et voila! Un gros problème.

This is the how. Many methods, such as “memory scraping”, exist that exploit plaintext that’s exposed in memory. Cybersecurity is hard.

So, what can be done to make the processing of this plaintext more secure?

Well, there is a handful of approaches that various secure enclave providers take. We’ll keep the example alive + analyse AWS’ Nitro Enclaves offering which is leveraged by the likes of Evervault, Crypto.com, Anjuna, etc.

Nitro Enclaves creates an isolated environment that’s a peer (just think linked in some way) to another EC2 instance (the “parent”) that you’re running. We load and process our sensitive data in this enclave.

As alluded to, this peer is a little different, more.. constrained.

For example, your Nitro Enclave has no internet access, no shell (e.g., SSH) access, no persistent storage and it runs its own kernel. Good luck to anyone trying to exfiltrate sensitive data from an enclave that isn’t connected to the internet.

Technical Detail: SSH = “secure shell”. A shell is a command-line interface (or CLI) that acts as an intermediary between a user and an operating system.

When you open up your mac “terminal” you ultimately use a shell program (e.g, “zsh” or “bash”) to interact with the OS.

SSH is a.. secure.. way to remotely access (or “tunnel” into) a given machine, remotely. We don’t want folk to do this when sensitive data’s involved.

The only way you can bi-directionally communicate with this secure enclave is via a “Unix Socket” (don’t worry about this) that connects to the enclave’s “parent” EC2 instance.

Why stop here though? “Defence in depth”, or, the more technical term: being a pain in the @$$ multiple times, is a strategy worth adhering to.

When “instantiating” (ie creating) a Nitro Enclave, a user specifies a number of parameters such as:

What application code the enclave will run.

The enclave’s software dependencies.

How much memory it will require.

How many CPU cores it will need.

These inputs are fed into a hash function that produces a ~unique “checksum” (ie hash, ie string of characters) based on its inputs. You may remember checksums from the Why Now post on Nix.

This cryptographic attestation is a bit of a game changer. Now, each time we want to use our enclave to process some sensitive data, we can first check whether or not the secure enclave’s inputs still produce the same hash.

If so, we know we’re running the same application code, with the same dependencies, in the same way. This allows us to cryptographically prove that our enclaves haven’t been tampered with in some way. Pretty cool!

As a wise Disney pop-sensation once said, with secure enclaves we have the best of both worlds: a way to provably protect data in-use, ~performantly.

Secure Enclaves are highly-constrained compute environments that allow for cryptographic verification (attestation) of the code being executed.

** Secure Enclaves — fin **

Once again, I’d appreciate love +/ lambasting on this post’s tweet to help get Why Now out into the ether further!

I’m at alex@tapestry.vc if you feel like saying hello / trading notes!